CONSTELLATIONS

There is a term for a different way of seeing constellations in the night sky, dark constellations. Instead of seeing a constellation as those points of light that we have learned over millennia to think of as images, we can think of this differently, but it takes a shift in how we typically see things, at least in our current times. This paradigm shift is an example of how we can shift our awareness and attention. It is a reminder that there is always another way to see reality. It is a shift in how we see the cosmos and what that might even mean for our sense of self and our mental health.

The way most of us see constellations in the night sky is based on creating images out of the stars we make patterns of. We agree on the picture, and the story, and share this over generations, even for thousands of years.

Take, for example, Orion and the three stars that form Orion’s belt in the night sky, perhaps one of the more easily found constellations each night.

Those familiar with this image will already begin to sketch out in their mind’s eye the familiar figure of Orion. Without showing you an overlay, do you see him– holding a shield and club as depicted in Greek myth? Or perhaps you see him drawing the string of a bow, as other cultures may have imagined him. Do you immediately picture the belt at his waist and the scabbard that hangs at his side?

Like a Rorschach test, we see images in the night sky–but culturally, we see many that have been expressed to us and reinforced over millennia. Like the fairy tales and myths we’ve told for thousands of years, this too is a form of storytelling and amplification. Perhaps it is even a way to map the brain–not just our awareness of where we are on the map, but who we are in the cosmos.

I say that it maps the brain because it helps us to ground ourselves culturally–in the tales we tell, the time we share, and in how those stories orient us in the world. They may guide us toward a belief system or toward a sense of connection with the cosmos and nature.

We tell stories. They may feel charming or help us to locate a constellation and get our bearings. But to the ancient people, they were likely very real representations of something they were looking for or believing in. Our myths revolve around the constellations–and perhaps these myths go back even further, to older stories still. They may have helped us make sense of the night, of our fears—or met a deep cognitive need to understand the world around us.

Perhaps the first stories drew themselves on the night sky and were found by humans–and even Neanderthals who saw something there.

MARKING OUR PLACE IN THE WORLD

One of the reasons that the constellations were useful to us is that they helped to locate ourselves in the world. They gave us orientation—helping us find our way back to our towns, villages, or the caves where we made some of our earliest artwork.

I say some of our earliest artwork, because although there is little surviving evidence to suggest we were making less permanent creations, I believe we were making art, toys, and carvings all along. Most of them likely didn’t survive because they were made with sand, wood, and the pigments found in nature.

My theory, as a lifelong artist, comes from studying the paintings in ancient caves like Lascaux and Chauvet. The artwork does not look primitive to me–it looks sophisticated. And sophisticated art that shows weight, gesture, and shading requires practice. This practice was done elsewhere, using more temporary means, or perhaps on the exterior of cliffs exposed to the elements–before the artist–or shaman–approached the interior cave wall.

This feels important to express because it challenges the idea that “modern” humans are a more recent phenomenon. There is no reason to dismiss the possibility that ancient humans were as intelligent and capable as we are today–and that among them lived Einsteins and Da Vincis.

One thing to underscore is that the inspiration for this article came from studying the negative handprints that our ancestors made in caves like Chauvet. These were not done by the simple act of putting a hand in pigment and then pressing it to the wall (and yes, these easier methods exist all over). Instead, the hand prints I’m fascinated by, were done by the opposite, by blowing pigment around the hand, which was used as a stencil, just as an airbrush artist might use a stencil today.

This led me to having an aha moment, that our ancestors had observed this somewhere. They weren’t looking at star constellations only, they were likely looking at the dark patches in the sky.

THE DARK CONSTELLATIONS

So let’s flip the image and think of what our ancestors may have seen. Let’s see if we can perceive the underworld that stretches up overhead–the unconscious that reveals itself even as we look up toward the lights.

What do I mean when I talk about dark constellations? We typically see constellations as clusters of stars—those pinpricks of light we’ve looked up at for tens of thousands of years.

In a world without GPS, roads, maps, and phones, the stars overhead guided us. Creating stories to help locate ourselves in the world makes incredible sense. If a moth can use the moon to navigate thousands of miles, then surely humans—gifted with big brains and imagination—used the night sky to find our way.

The lights in the sky would have also given a sense of comfort and predictability. To our ancient ancestors, survival depended on being able to predict the seasons and the movement of animal herds.

The paradigm shift though is this. In drawing images with the stars, perhaps we are ignoring other things ancient people would have been more aware of as well.

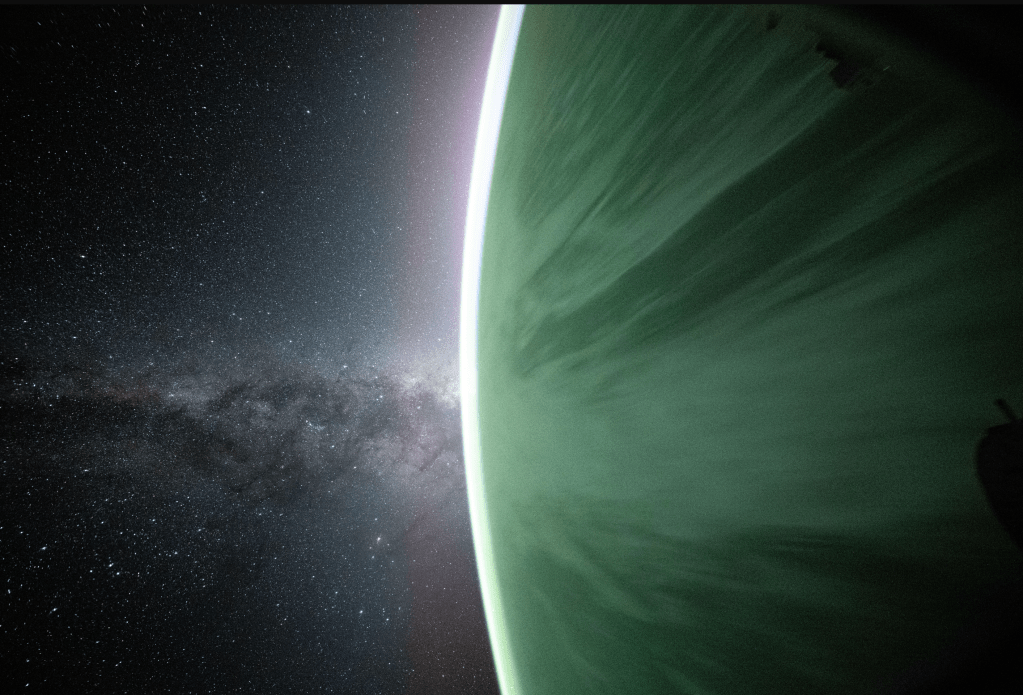

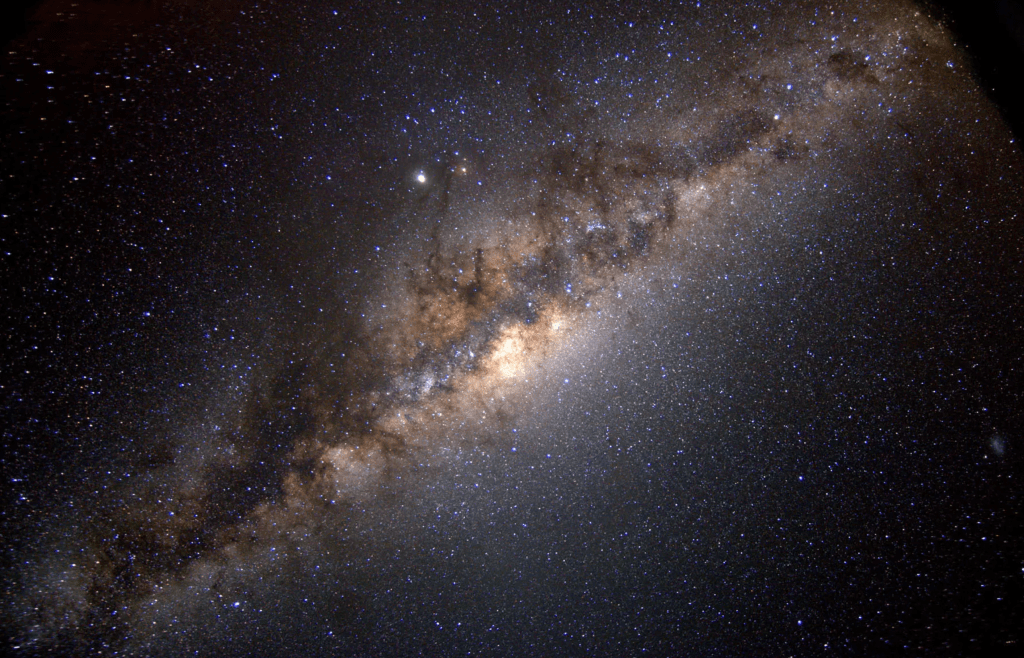

The band of the Milky Way galaxy could be seen across the night sky as well, but we often tend to see the positive, lit starry area of the Milky Way and ignore the dark patches, the clouds of gas and dust that occlude more stars behind them.

I don’t believe our ancestors would have ignored these dark areas, as an artist I can’t help but see imagery in these dark areas far more easily than I can see in the pinpricks of light, so I questioned what might they have seen.

In fact, we do know that many cultures in the southern hemisphere paid close attention. Aboriginal cultures across Australia, for instance, identify dark constellations—the shapes of the Milky Way that are negative but outlined by the lighter portions of the Milky Way cloud. One famous example is The Emu in the Sky, formed from dark patches not the starry pinpricks of light.

WHY ARE DARK CONSTELLATIONS IMPORTANT?

Why is this interesting to me? It is because it speaks to the mystery we all find ourselves within. We think we see the world clearly, and yet even something as seemingly simple as how we see the night sky can be inverted. We can question how we have perceived the night sky and how our stories have been told and shared, even while we ignore the imagery that is intermingled between the stars.

I think that dark constellations are a good metaphor for the unconscious and perhaps the collective unconscious as proposed by Carl Jung.

If the collective unconscious is like a river of imagery that flows throughout humanity, then one thing that would universally connect us, is that we saw the Milky Way overhead flowing like a river through the night sky. In that celestial river, our curious minds could pick out images, gods, snakes, dragons. We might see even the hand of God reaching to man.

We believe that we are seeing everything because we are studying the movement of the stars and see the pictures in our heads. We hear the stories from the past and we tell them to our children, and all the while, we are losing more and more vision of the night sky as it becomes occluded by light pollution. As stars fade from view, the band of the Milky Way, which grounded us for tens of thousands of years –is now barely visible in the night sky.

Those images that we told stories about, the gods and goddesses we saw, are still there, but recede from awareness as our vision narrows and we look to four walls, and devices. We become more consumed in our work, our programs on Streamberry, TikTok, our cell phones, and our Instagram feeds.

As we focus downward, we become disconnected from the world around us, and the dark constellation, which may hold stories going back tens of thousands of years. It may be the Akashic record, a celestial illustrated scroll that flows overhead like a river that we are forgetting.

We are annihilating our connection to the cosmos and the past and our place in the world, and then wonder at our growing apprehension about the future. Even more troubling, our attention is being hijacked. What once connected us, myth, nature, and the cosmos—is replaced with synthetic distractions, digital connections that feel false. Our curious brains still seeking connection and our place in the world, find our anxieties amplified, and our disconnect ensured.

The dark constellations remain, but fade like whispering voices at the edge of our consciousness. They ask us to remember and to pay attention to the things that connect us.

PARADIGM SHIFT

In discussing the constellations and dark constellations, I am challenging the way we see the world, and also hoping to bring to mind the feeling of reaching back in time to the ancestors who lived through the most difficult circumstances and still found meaning and purpose in the world.

They looked for connection, but this was likely easier than we think because our big brains were primed to find connection and meaning. This may be part of what we take for granted, that we didn’t necessarily need to seek connection in the past, but always felt we were part of everything.

The modern world is full of conveniences, and also has taken away much of our connection to the natural world, and our part in it. We see ourselves as separate from nature, and we are not. We refer to other creatures on this planet as animals, as if we too are not one of the animals, forgetting we too are one of the great apes. This is not to diminish us, but to underscore that seeing ourselves as separate from nature, and the cosmos, is part of our discontent.

All these things challenge how we see ourselves in the world, and speak to the ongoing challenge of reflecting on our human experiences, and this life journey we are on. The goal is to question how we perceive ourselves, and our place in the world, so that we can deepen our understanding of who we are, by reminding ourselves where we came from, and some of the universal things, that we share.